Imagine for a moment that you were living during a time of war. You, and the rest of your community, have been forced to live in an area far too small for your numbers. You have heard rumours that the overcrowding is not an issue because your enemies plan to murder you very soon. Imagine also that you have been placed in charge of your entire community, and it is your job to arrange housing assignments, work assignments, and to do your best with maintaining some semblance of order and normalcy in a completely upside down world. Imagine that one day your overlords come to you and say that if you can convince your community to turn over all of its children, the rest of the adults can continue to live. What would you do? In numbers, you are being asked to sacrifice 20,000 children, the elderly and the ill to save upwards of 70,000 adults. Except, the adults you’ll be saving are the parents of those children.

This is the position in which Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Judenrat (Jewish Council) in the Łódź Ghetto in Poland found himself in the fall of 1942. He gave a famous speech to the parents of the Ghetto - “Give Me Your Children” - in which he asked the parents to voluntarily hand over their children - to be murdered - so that they could continue to live. Why? In order to keep the ghetto in existence, it needed to be seen as a “useful” and industrial ghetto. If that was the case, then there was no need for children, the sick or the elderly. Thus, the deal was, if these groups were voluntarily turned over, those capable of working (10 years of age and up) would be allowed to work, live, and avoid deportation. Unsurprisingly, the parents did not agree. But this did not save the children. Rumkowski ordered that the children under 10, the elderly, and the sick, be removed from the Ghetto. They were sent to Chelmno, a death camp, where they were gassed to death - mostly in makeshift gas chambers in the back of cargo trucks.

While turning over the children, elderly and sick did buy the Ghetto more than a year and a half of reprieve from deportations, it also allowed the ghetto to produce more than $14 Million USD in revenue for the Nazis during the same time period — in 1940s values! In the end, Himmler overruled the “deal” that Rumkowski had struck and ordered the rest of the ghetto deported to Auschwitz. How do we today determine what was a moral or immoral decision under such circumstances?

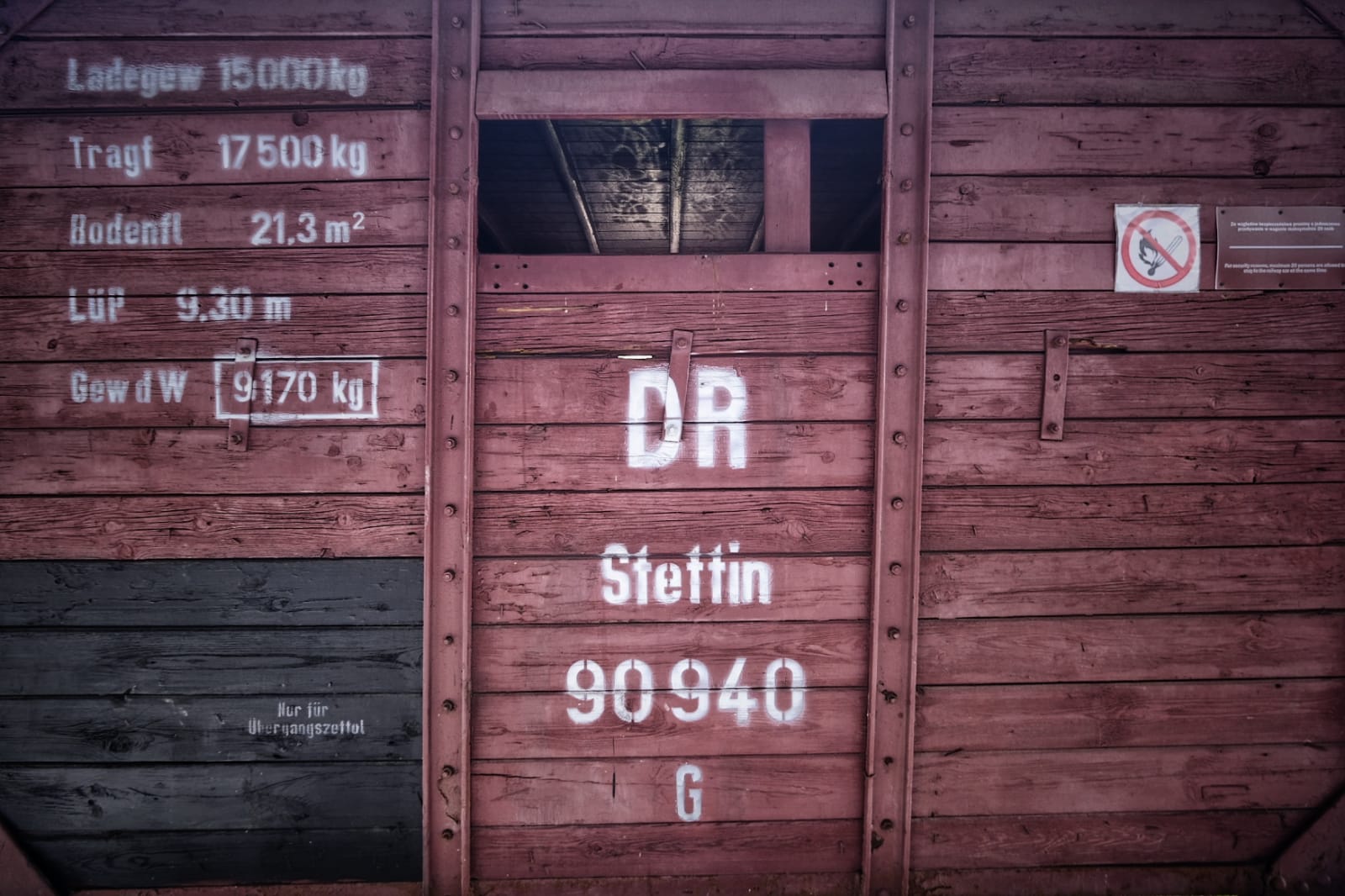

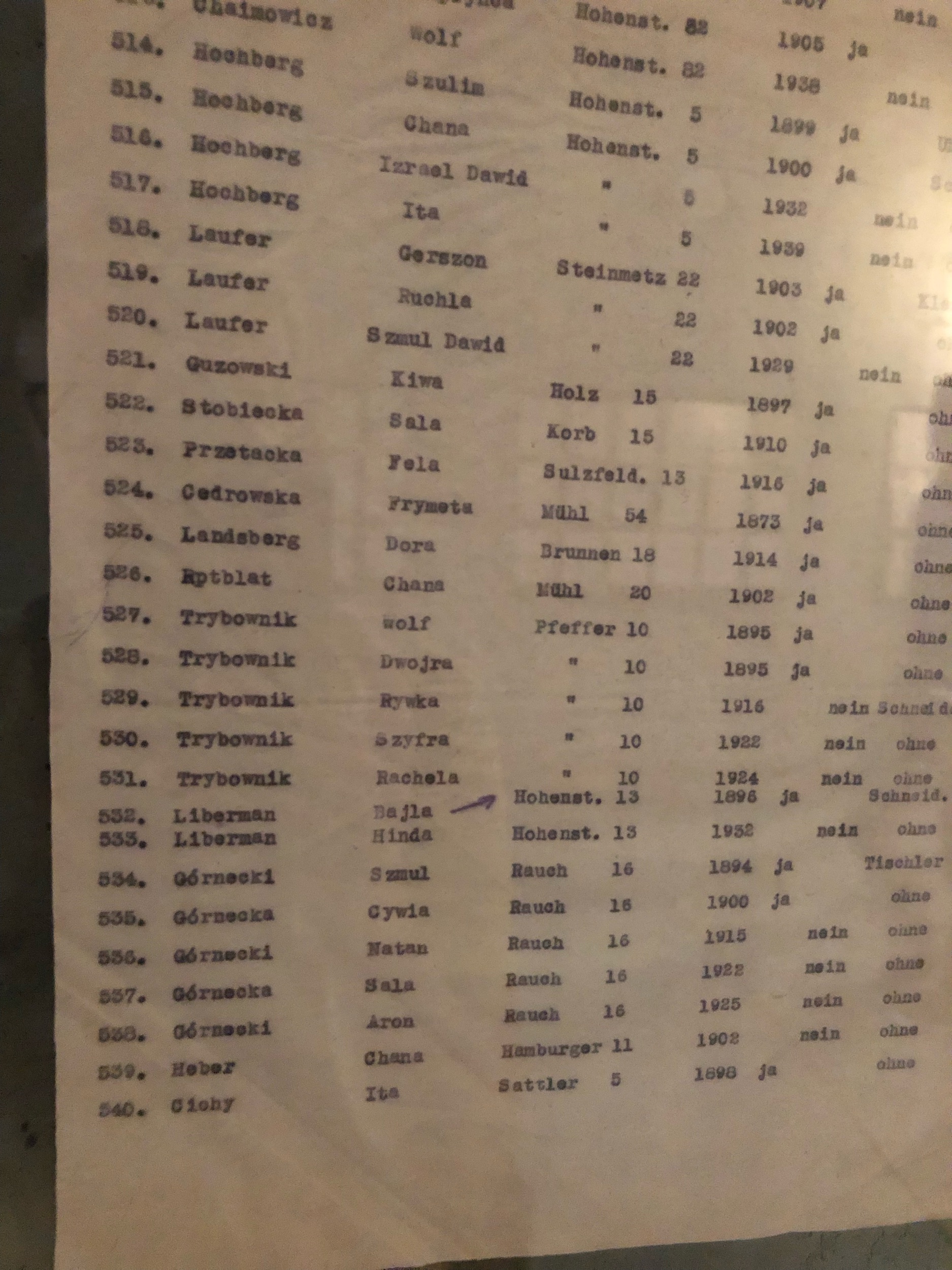

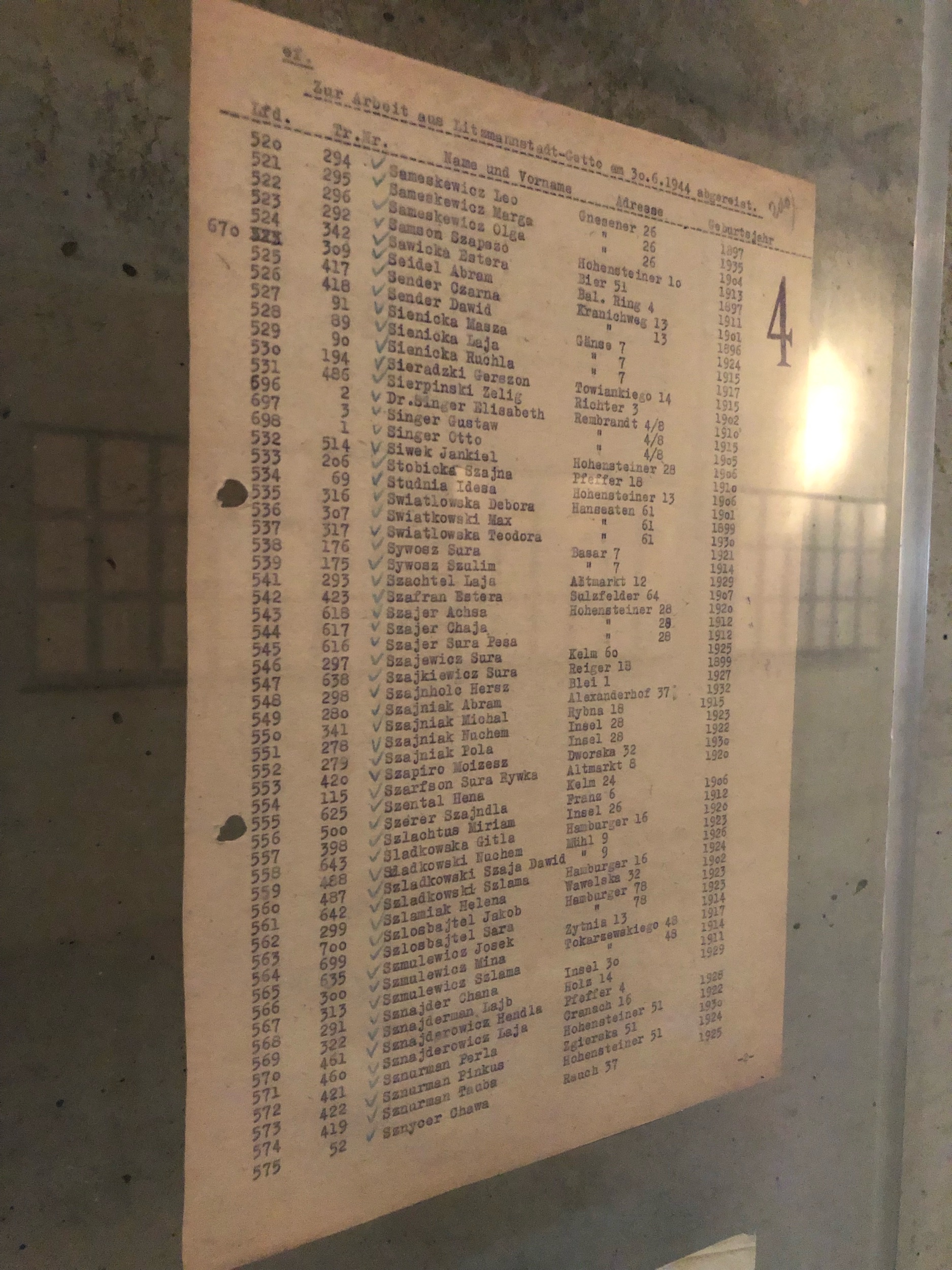

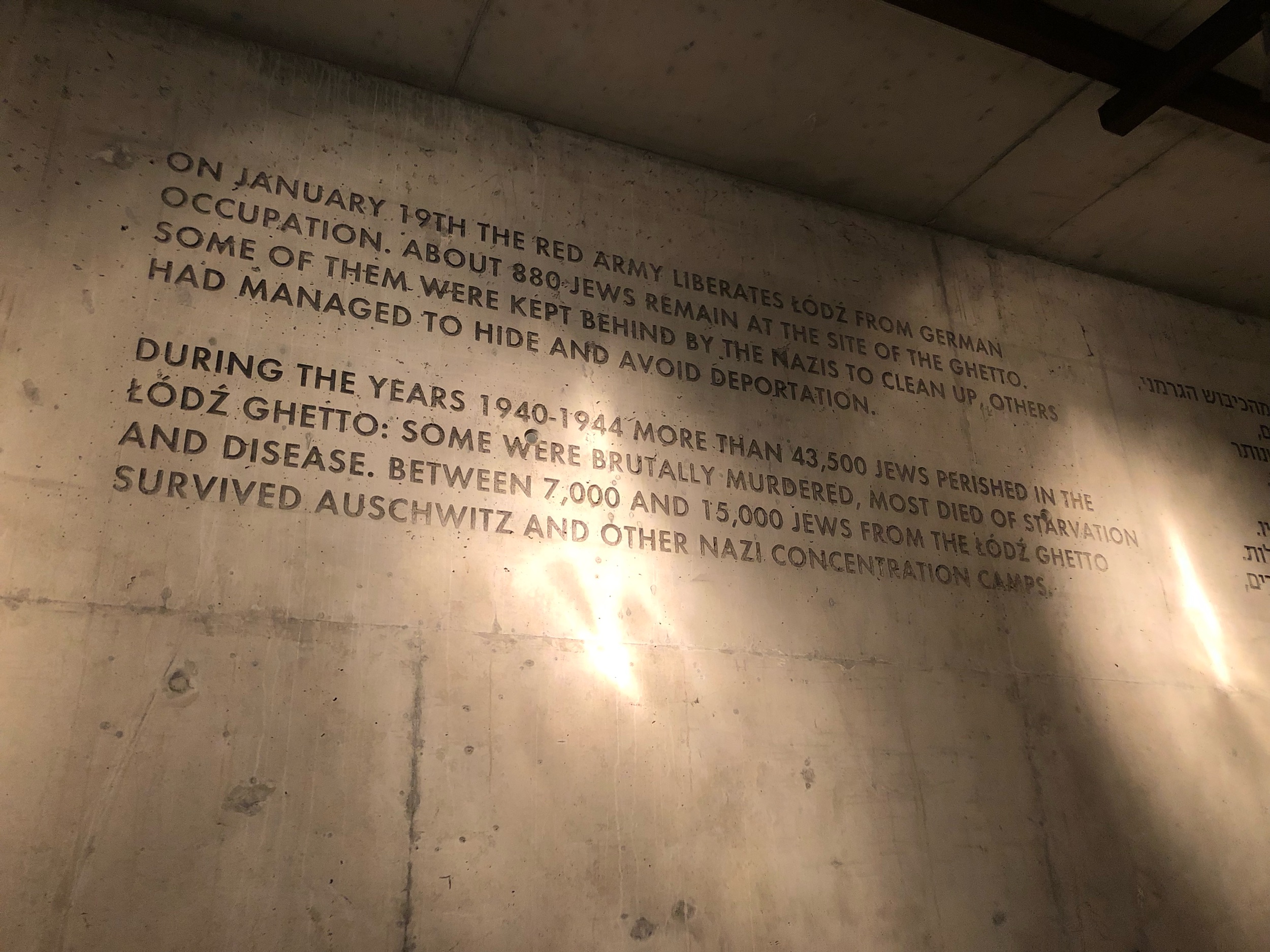

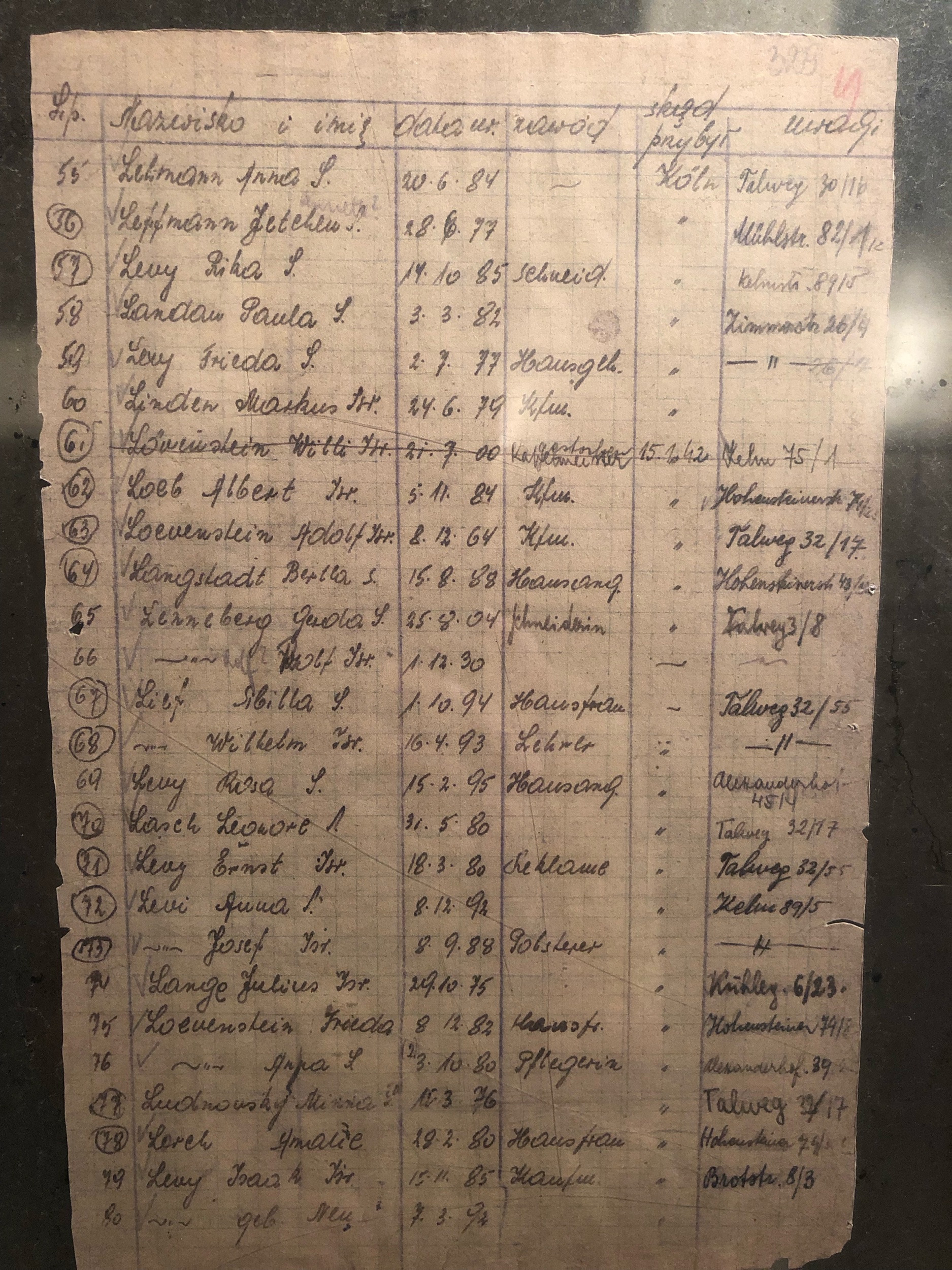

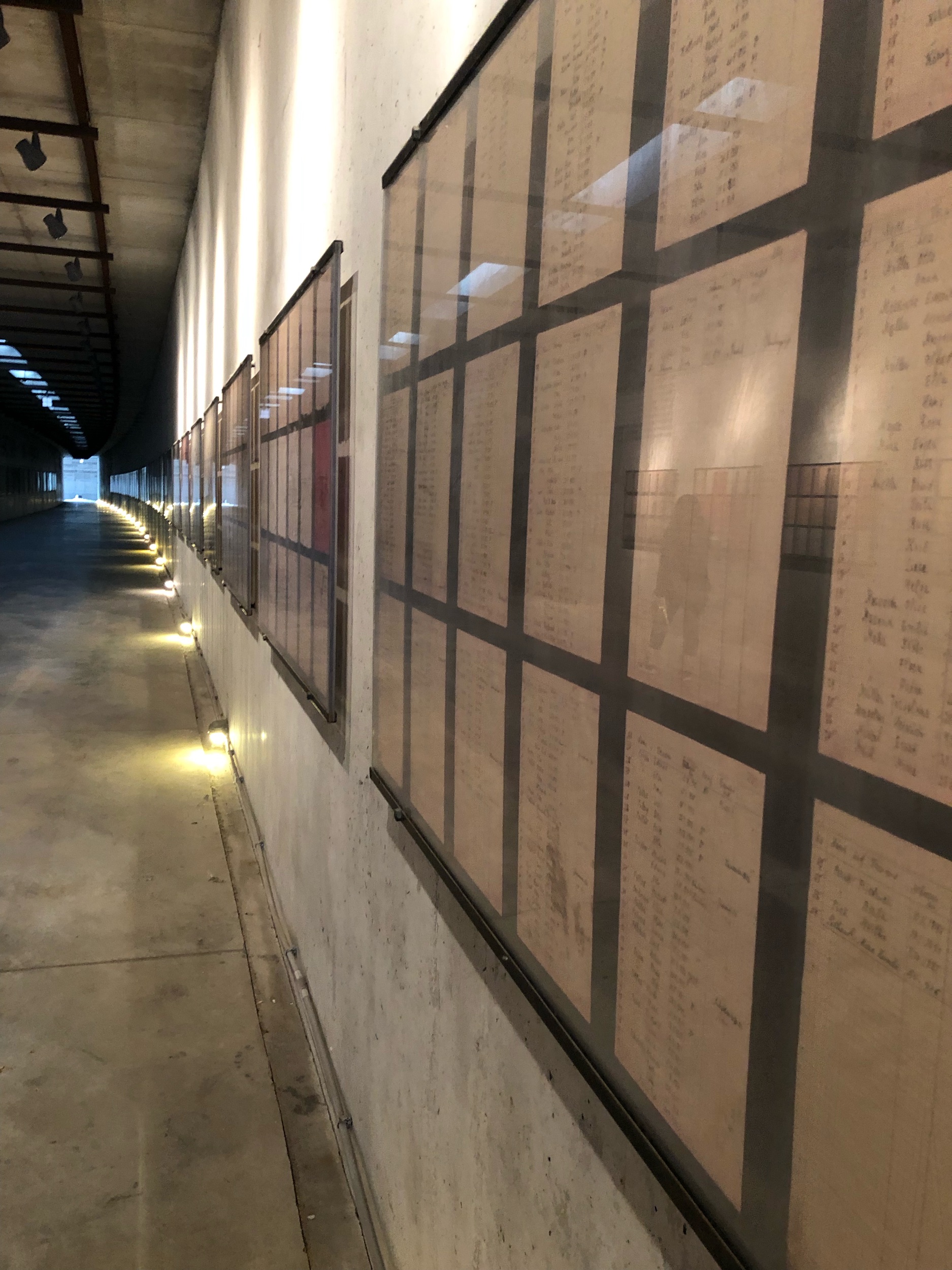

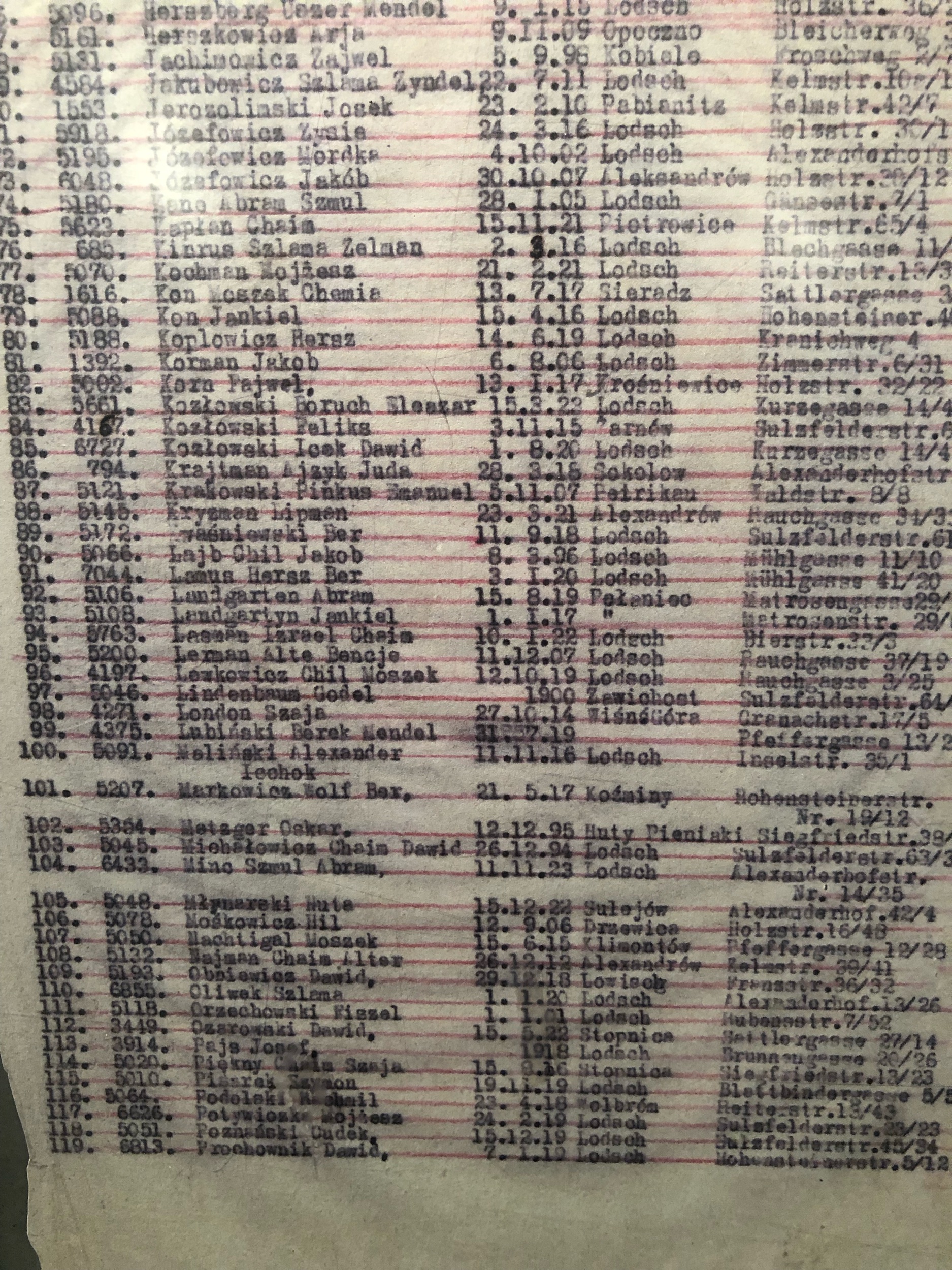

Today we listened to this story, considered the magnitude of being faced with such impossible decisions, and then visited a memorial to those who were deported from the Łódź Ghetto. The memorial consists of three parts. There is a train station that houses a small museum showing the Ghetto. The memorial is along the train tracks - still in use - so while you are there, every once in a while a train goes by. On a set of train tracks outside the station sits a series of 1940s cattle cars, the same kind of cars that Jewish people were packed into - 100 per car. We stood inside one of the cars - approximately 20 of us - and tried to imagine - impossibly - what it would be like for there to be 5 times as many people in there with us. Walking away from the cattle car you enter a hall of memory, which is lined with page after page after page after page of neatly typed or written lists of names. They are the meticulously prepared lists that dictated who would be put onto the “shipments” out of the Ghetto on which dates. I can’t imagine how long it would take to read each and every name.

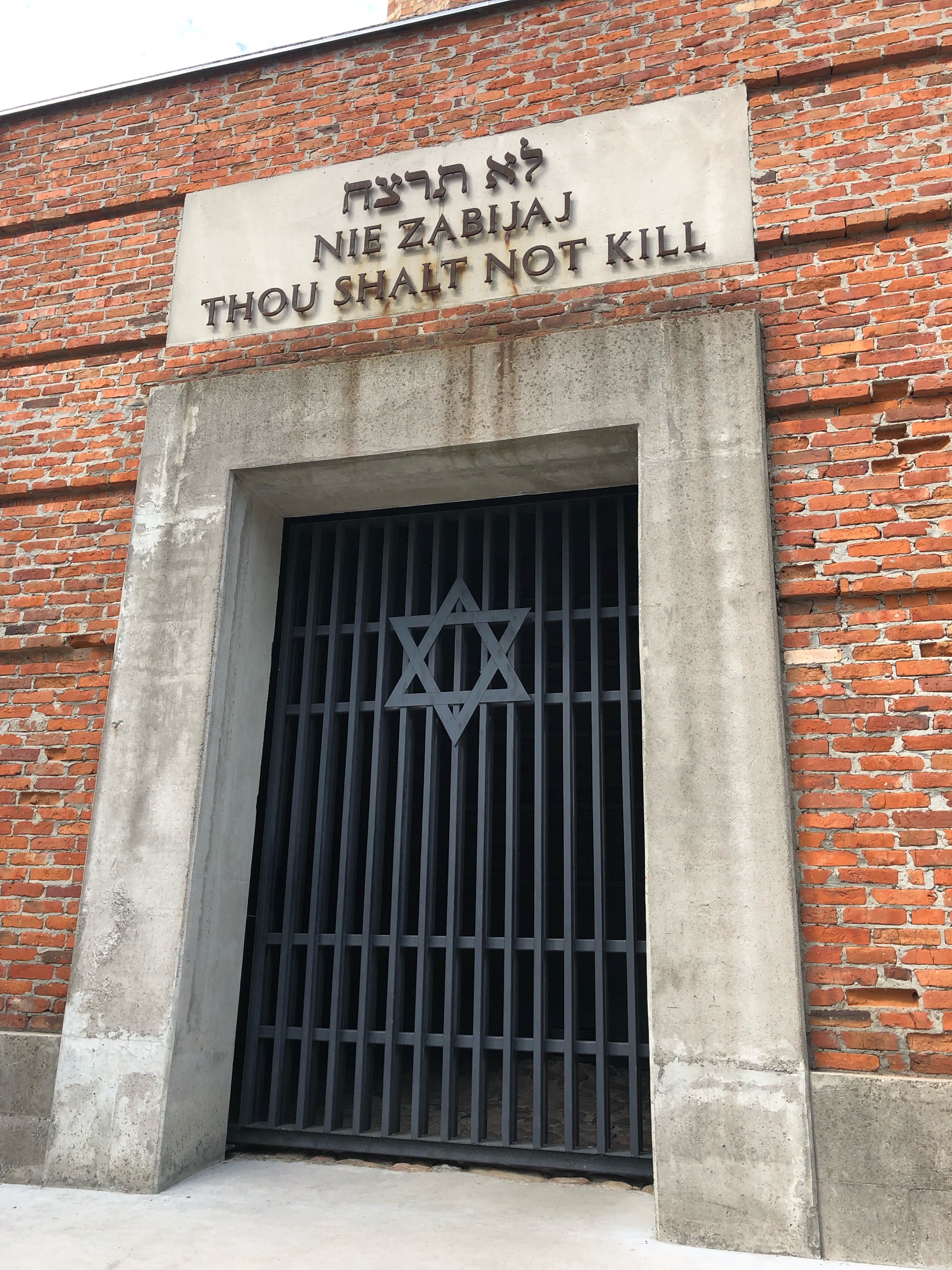

At the end of the tunnel, there is a hall of names - names of the places from which people were sent to the Ghetto. Entire towns and communities, families, wiped from the Earth forever. The light coming in comes down from a tall pillar - which, from the outside, looks like the chimney of a crematorium. There is a gate, with the Star of David on it, and the end of this tunnel represents the fate that the majority of the Łódź Ghetto inhabitants met - death followed by unceremonious incineration.

As with many Holocaust memorials, the Radegast Station memorial for the Łódź Ghetto deportations is really only as impactful as the narratives and stories that you bring with you to the site. This is one of the challenges of Holocaust Education. Visiting these sites can reach a visceral level that can never be reached through reading alone, and yet, that level can only truly be experienced if the visitor has done some reading before arriving. Visiting this site left me wondering how it is perceived by individuals who visit without the narratives, without the bigger picture. If they step inside of that cattle car alone, how do they feel? If they don’t know what awaited the passengers at the other end, can they even begin to imagine the terror of that experience? Today it is just an empty cattle car.

We perhaps got some hint of how people may perceive this site. While we were there, two things happened. The first was a young family out for a walk. While we were sitting on the steps discussing the impact of the memorial, the family walked by - a mom, dad, dog, and a young child driving one of those motorized cars for kids. He was honking the horn, driving on the sidewalk of the memorial, and when they got closer to the train station section where the cattle cars sit, he was driving around in circles at the base of the station - clearly within the boundaries of the memorial site. Perhaps the family lives nearby and this is just the most logical place to go for their evening walk? There are what appear to be apartments being built right next to the memorial and I also wondered what it would be like to live there. Could you live there if you were aware of the history and meaning?

The second event was somewhat more jarring. A car with two young men drove past and parked right on the sidewalk of the memorial. They then got out, sat on their car and cracked open two beers. To fully understand this, you have to realize that this memorial is down a dead end street, it is right on functioning train tracks, it is not a grassy area or a park. In other words, it’s not a memorial that happens to be in a place where you’d also want to just relax and have a beer. After a while, another young man walked past the car and from the body language of the conversation that followed, it appeared that this third man was trying to tell the two beer drinking men that this was an inappropriate place to sit and have a beer. The third man gestured back towards the cattle cars, pointed to the dates of the war inscribed on the wall behind where the men were standing and shrugged his shoulders as if to say “this doesn’t seem to be an appropriate place for you right now.” This man continued on, and a few minutes later the two young men got back into their car and drove away. To do so, they had to drive past our group, which was still sitting and discussing. As they drove by, the man in the passenger seat made eye contact with me and then proceeded to smile a rather menacing smile and wave. I don’t know how to describe it. It was one of those things where if you could confront the person they would probably say “What? I was smiling at you, and waving, what is so wrong about being friendly?” And yet, if you saw that smile, you would instantly know that it was not a friendly smile. Up until that point, I had thought perhaps they just didn’t know where they were. Maybe they were just looking for a place to hang out and drink beer. But the way he looked at us, the way he waved, it made me feel as though they really did know where they were, and that they had come there on purpose. Hopefully, I am wrong in how I interpreted the situation, but I fear otherwise. For me, while the whole visit had been quite powerful, the moment of seeing him wave was the moment that hit like a sucker punch. It is one thing to learn about the atrocities of the past, and to question how on Earth humans could ever be so cruel to each other - but it is another to then in a moment be faced with the answer - we can do this because we are capable of disregarding the others’ feelings, of dehumanizing them, feeling contempt towards them, and refusing to empathize. I can think of no greater insult to the victims of the Holocaust than the fact that we, as humans, have failed to learn the lessons inherent in their deaths, and that we continue to treat each other in ways that made the Holocaust possible in the first place.

More Reading:

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/give-me-your-children-voices-from-the-lodz-ghetto

https://speakola.com/ideas/chaim-rumkowski-give-me-your-children-1942

-

August 2020

- Aug 5, 2020 The Social Psychology of the Holocaust Podcast Aug 5, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 An Open Letter About Holocaust Education in Canadian Schools May 21, 2020

-

July 2019

- Jul 8, 2019 Treblinka Jul 8, 2019

- Jul 7, 2019 Łódź Memorial: Radegast Station Jul 7, 2019

- Jul 6, 2019 Berlin & Wannsee Jul 6, 2019

- Jul 5, 2019 Berlin & the Monument for Homosexual Persecution Jul 5, 2019

- Jul 4, 2019 Berlin Jul 4, 2019

- Jul 3, 2019 Meeting with Holocaust Survivors in Toronto Jul 3, 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Canadian Society for Yad Vashem Leaders of Change Program Jul 1, 2019

-

December 2017

- Dec 2, 2017 How Taking A Course About the Holocaust Just Might Save A Life! Dec 2, 2017